A Cuckoo in the Royal Nest; who was Frederick William Blomberg?

By Emma Rutherford | 12 September 2023

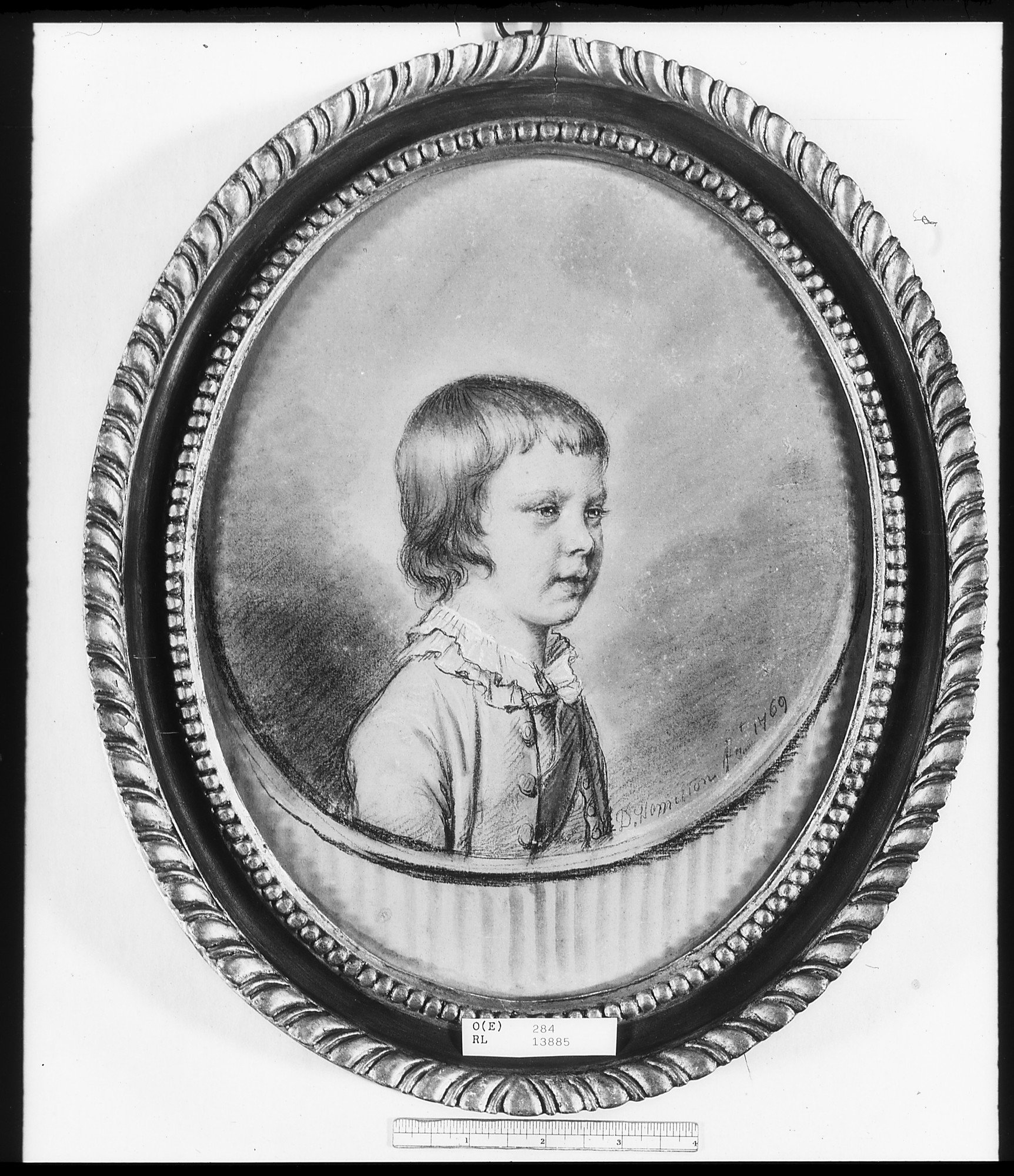

Fig. 1

On a visit to the royal nursery in 1769, one would have met four princes and two princesses, including George, Prince of Wales (later King George IV) – who had been born born August 1762.[1] Born just a year before this first child of the young Queen Charlotte, one would have met another boy, indistinguishable from his apparent siblings. This boy was Frederick William Blomberg, the child portrayed in this drawing (Fig.1) – who had been evidently welcomed into the nursery as a toddler by King George III and Queen Charlotte. The sketch was drawn by Hugh Douglas Hamilton (1740-1808), who in the summer of 1769 had been asked to draw the four princes, along with their parents (Fig.2). These drawings now reside in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the young princes shown in feigned oval frames, their parents in informal clothing with the king shown without any orders or ribbons. It is fascinating that the only drawing missing from this group is the one of the mysterious Blomberg – the cuckoo in the royal nest.[2]

Fig. 2 Left to right: William, Duke of Clarence (1765-1837), 1769; Edward, Duke of Kent (1767-1820), c.1769; Frederick, Duke of York (1763-1827), Jun 1769; George, Prince of Wales (1762-1830), signed and dated 1769; George III (1738-1820), signed and dated 1769; all by Hugh Douglas Hamilton (1739-1808) - Royal Collection Trust

Called Frederick William Blomberg, the child had been born in 1761, the record of his baptism being recorded at St Margaret’s, Rochester. His parentage, however, remained a cause for speculation throughout his life and beyond. One version stated that he was the son of a certain Major Frederick Blomberg, and his wife Mellissa Laing. Major Blomberg was said to have drowned, leaving the child to be raised by Queen Charlotte – but why would the young queen have taken on a child when she was already a mother to three boys of her own (confusingly for the young Blomberg, one called Frederick, another William)? The supposed parents do not seem to have had close connections to the royal couple. Other sources give the child’s father as Friedrich Karl August von Blomberg (d.1764) but with his mother not dying until 1803, it is strange that she would not have raised him.

One explanation has made sense during Blomberg’s lifetime and beyond – that he was in fact the illegitimate son of George III. Baptised two weeks after the King’s marriage, and one day after his coronation, it is unclear exactly when the child entered the royal nursery. He was certainly there in 1765, as in January that year Lady Charlotte Finch, known affectionately as 'Lady Cha'), noted that Queen Charlotte wished to have some separation for Blomberg (then only four years old) from the rest of the royal children; ‘The Queen determined to take Master Blomberg and allow him 50 pds a year and put him under Mrs. Cotesworth’s care.’[3] Mrs Cotesworth was the sub-governess to the royal children, while Charlotte Finch ran the royal nursery (she can be seen in the painting by Zoffany, the only non-royal included, holding a baby, probably Ernest (1771-1851), later Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover (Fig. 4).

Whilst Blomberg’s striking resemblance to his adoptive siblings was noted, no evidence has emerged to clarify his parentage.[4] One explanation for his close likeness to the royal children was that, if not the son of the King, he could have been the offspring of one of the King’s brothers – most likely Edward, Duke of York. In 1760, as a handsome naval officer, Edward had enjoyed a reputation for his affairs with many women and may well have fathered a child born in 1761. If the child was not the King’s own illegitimate child, his sense of duty may have informed his decision to bring his nephew up among his own progenies.[5]

Blomberg’s royal upbringing and financial support from this grand family assisted his rapid rise in his chosen career in the church. After a Cambridge education, his positions included including Prebendary of Bristol (1790-1828) and Westminster (1808-1822) and Chaplain to George, Prince of Wales (the future George IV) between 1793 and 1830. His ambition cannot be explained by his talent as a preacher – as one contemporary observer noted, he was better suited to a career as a musician; ‘he was poor in his sermons, […] on the fiddle had few superiors.’ On Blomberg’s death in 1847 (after he had also served Queen Victoria as Canon Residentiary of St Pauls and as her personal chaplain), the Gentleman’s Magazine wrote a tactful obituary. Ignoring rumours of his ancestry, they simply stated that he lived ‘in intimate association with the children of King George III who always retained great affection for him’.

Speculation continued into Queen Victoria’s reign as to exactly who Blomberg had been and two books were published which investigated his close association with the Royal Family (The Unseen World in 1847 and The Journal and Memories of Thomas Whalley in 1863). Woven into the tale was now a ghost story, based on another book published shortly after Queen Charlotte’s death in 1818 (fig.6).[6] This story stated that, following the death of his father, Major Frederick Blomberg, who allegedly drowned enroute to Dominica, his ghost then supposedly appeared to the governor of Dominica to tell him the whereabouts of Blomberg’s two children, the orphaned offspring of a secret marriage, who were housed with a distant English relative. Moved by this story, Charlotte was then allegedly inspired to adopt the boy (although no mention is made of the fate of the other child).

Fig. 6 T. M. Jarvis, Accredited Ghost Stories, London, J. Andrews, 1823

Apparently sketched in the Royal nursery, the little boy in this drawing (fig.1) looks lost and withdrawn. He has been portrayed surrounded by his accomplishments – including a violin, a notebook and a porte-crayon – some of the activities provided by the busy royal nursery, which at the time boasted a huge number of staff (from cradle rockers and dressers to reading masters, pages and porters).[7] Only one other image exists of Blomberg – a painting sold at Christie’s in 1982 – by Richard Brompton (1734-1783) (fig.7).

While we may never know the exact circumstances surrounding Blomberg’s presence in the royal nursery, the fact that he was welcomed into this exclusive environment is due cause for speculation surrounding his parentage. If he was not a child of George III’s, his presence illuminates the royal couple’s sense of duty – either to an orphaned boy or to the offspring of one of George’s brothers. Whatever the truth behind the boy’s background, this is one storyline where fact was stranger than fiction – take note Bridgerton…

[1] The others would have been: Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany - born August 16, 1763; Prince William (later King William IV) - born August 21, 1765; Charlotte, Princess Royal - born September 29, 1766; Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn - born November 2, 1767 and Princess Augusta Sophia - born November 8, 1768.

[2] This group, said to have been commissioned by George III, is noted in O(E) : Oppé, A.P., 1950. English Drawings in the Collection of His Majesty The King at Windsor Castle, London, p. 54, the one of the Queen illustrated as plate 6.

[3] GEO/ ADDL 21/ 181.

[4] Alumni Cantabrigienses noted that Blomberg was a constant companion to the royal children and that he resembled some of them. He was admitted to St. John’s College in 1777.

[5] Although George III has been suggested as the child’s father in many sources, his infatuation with Lady Sarah Lennox in the years leading up to his marriage may have precluded any other extra marital affairs. It would also have been wholly out of character for George III.

[6] This story was published by Jarvis, T. M., Accredited Ghost Stories, London, J. Andrews, 1823, pp. 138-141.

[7] Details of staff are listed by Bucholz, Robert, "The Royal Nursery (1737-1768)" (2019). The Database of Court Officers 1660-1837. 99. https://ecommons.luc.edu/courtofficers/99